By: R. Collins

When time takes its toll on natural landscapes and their existing ecosystems, there are innovative techniques available with the ability to slow the process using materials that blend into the background. For the Park District of Highland Park in Chicago, there was a vision to save a landscape in such danger of being lost: Rosewood Beach.

Newly renovated in 2015, Rosewood Beach—once a rugged and eroding segment of the Lake Michigan shoreline—has already won multiple accolades for the success of its rebirth, such as the American Shore and Beach Preservation Association 2016 Best Restored Beach award, and the 2016 Chicago Building Congress Merit Award.

The beach is gathering interest for a number of reasons; the foremost being the smart, simple, and non-invasive design of the new sandscape that allowing beach-goers and the natural ecosystem to interact in harmony.

Creation of the new site was in part a collaborative effort between the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, or USACE, and Woodhouse Tinucci Architects in Chicago; both of which used sustainable practices and materials to ease construction in a non-disruptive direction.

The USACE’s civilian and army engineers use sustainability as a guiding principle during waterway renovations around the world, and partnered on the project through its Great Lakes Fishery and Ecosystem Restoration program. Paired with Woodhouse Tinucci’s sustainable design methods—which have been used to construct the New Congress Theatre in Chicago as well as the University of Chicago’s Regenstein Library—Rosewood beach underwent a renovation that serves as a testament to the concepts of sustainable design and construction.

Both the USACE and the firm were overseen by Rebecca Grill, manager of Natural Areas at the Park District of Highland Park, who described the project as an effort to inspire beach visitors to learn about and protect Lake Michigan and its beaches.

The $14.5 million renovation resulted in the shoreline being split into three distinct coves, which Grill said serve a separate purpose in beach utilization.

The southernmost and middle coves are meant for recreational use, complete with volleyball nets and the middle cove for safe swimming with lifeguard surveillance, concession center, restrooms, an ADA-compliant play structure, and a Mobi Mat providing roll-out surfacing for wheelchairs to access the lake.

The north cove, deemed the “nature cove,” is a passive beach reserved for nature studies, summer camps, and natural wildlife. It also is host to a sustainably-built, low profile interpretive center which holds many of the area’s field trips and nature classes. The interpretive center hosts nearly 500 children in environmental science classes in the spring to study Lake Michigan’s habitat, which is accurately displayed through the three-cove-system.

“I really do think of it as nature’s beach and people are here to enjoy that,” said Grill.

While each cove serves a different purpose for beach visitors, their design had to consider how to protect them from the forces that eroded the previous landscape. To ensure their safety, the USACE constructed breakwaters 200 feet from the Lake Michigan shoreline to prevent erosion of the coves, which were constructed using more than more than 65,000 cubic yards of sand, laid in place of the old rocky shoreline.

Grill, in addition to her role as manager with Park District of Highland Park, was one of the Lake County residents who took it upon herself to protect the natural processes already in motion at Rosewood Beach. She has been conducting research on the animal and plant species—some of which are not normally found in Illinois—that have made Rosewood Beach home since 2005, and regularly visits the beach to update the progress they are making re-acclimating to their new habitat.

“We’re at near record lake levels right now and we still have a great beach habitat, which is provided by the Army Corps’ structures out there,” said Grill.

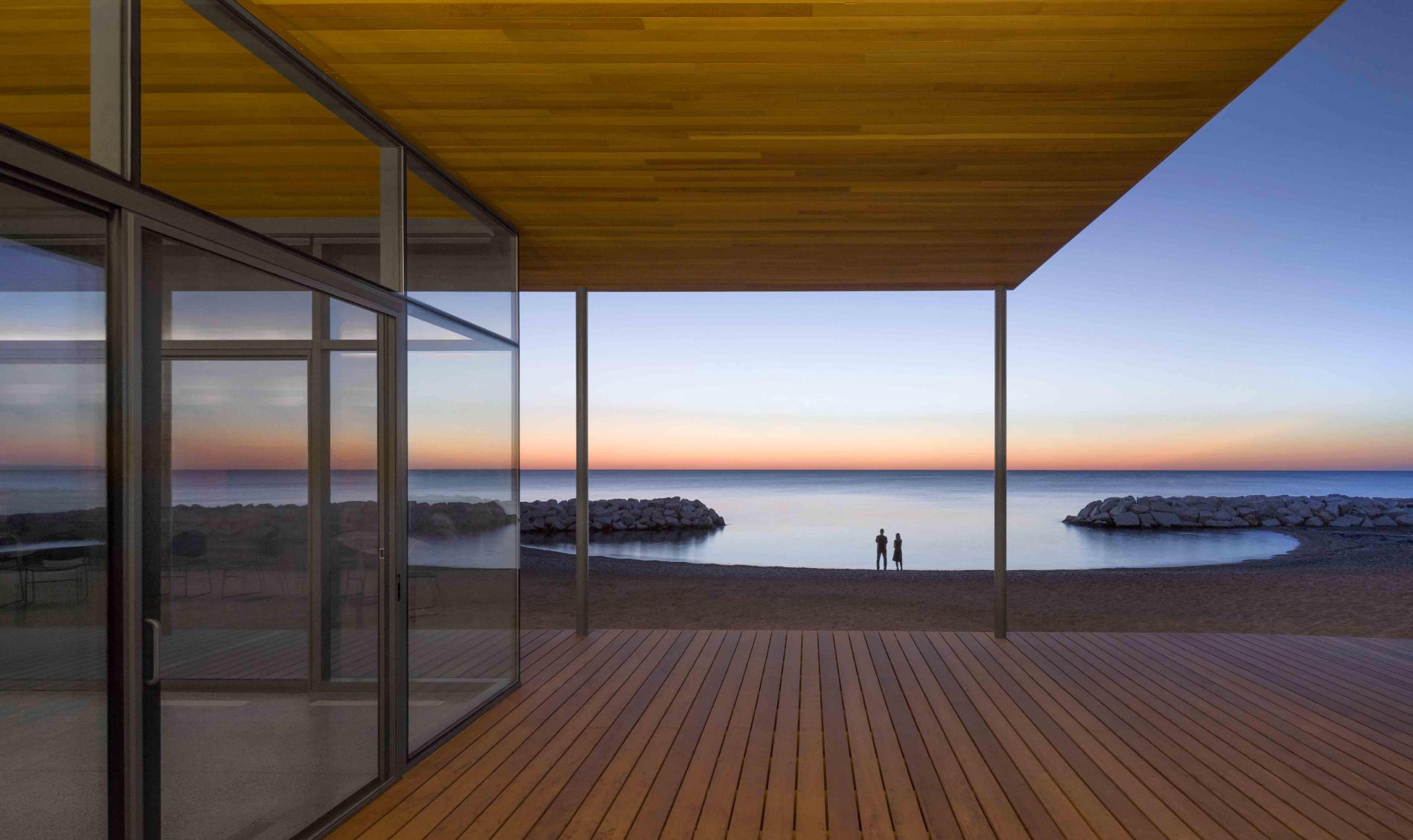

A wide array of natural materials can partly be credited to this smooth transition from the old landscape to its updated form. With the design plans provided by Woodhouse Tinucci Architects, the new Rosewood Beach utilizes materials such as rough field stone and cedar, as well as Ipe Brazilian hardwood decking to make the boardwalk dense and durable.

When working with Woodhouse Tinucci, Grill said one of the main goals of the design of the structures on shore was to blend into the natural landscape as the additions to the natural habitat did.

The buildings are crafted to be long, low, and cased in mullion-less glass to allow viewers an unobstructed view of the lakefront. The interpretive center differs from the rest in that it is geothermally heated and cooled, and is sheathed in Ornilux bird-safe glass shipped from Germany, which allows viewers a 180 degree view of the shoreline.

Grill said since Lake Michigan is a busy fly zone for migratory birds, it was important that the glass used at the center help prevent accidents by using intricate web-like etchings in the glass that alert birds to a stationary object.

The final product is a beach landscape that satisfies the needs of beach-goers, educators, and Lake Michigan’s natural ecosystems all year-round. The process of intertwining new technologies with both natural materials and environment has redefined one of Chicago’s most promising beaches as a small sanctuary for those who use it.

“I would say, in many ways, that life has returned to Rosewood beach,” said Grill.

Park District of Highland Park owns and manages more than 700 acres across 44 parks in Illinois, with a vision of inspiring environmental stewardship and education, enriching community life through healthy leisure pursuits, and to exceed the public’s expectations of parks and recreation experiences. The organization is governed by an elected Board of Commissioners, while daily operations are managed by professional staff.