In May 2019, the overall value of construction work done in the United States totaled more than $1.29 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Value of Construction Put in Place Survey. In the same month, Michigan’s second largest city, Grand Rapids, spent $13 million on new construction alone and has undergone some measures to ensure a sustainable future in tandem with its continuing developmental upswing. It is one district among a network of urban areas participating in the 2030 Challenge for Planning, which is a national initiative focused on carbon-neutrality, and cutting water usage and transportation emissions in half by 2030.

In May 2019, the overall value of construction work done in the United States totaled more than $1.29 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau’s Value of Construction Put in Place Survey. In the same month, Michigan’s second largest city, Grand Rapids, spent $13 million on new construction alone and has undergone some measures to ensure a sustainable future in tandem with its continuing developmental upswing. It is one district among a network of urban areas participating in the 2030 Challenge for Planning, which is a national initiative focused on carbon-neutrality, and cutting water usage and transportation emissions in half by 2030.

To continue the effort, the United States Green Building Council’s West Michigan Chapter and AIA Michigan organized a lunch-and-learn event in June 2019 called Underneath it All: The Gravity of Embodied Carbon. The Grand Rapids-based event aimed to examine the issue of embodied carbon—or the greenhouse gas emissions from construction and renovation—which affects every aspect of a building, from insulation to final finish.

What is Carbon? Embodied Carbon refers to the carbon dioxide emitted during the manufacture, transport and construction of building materials, together with end of life emissions.

Matthew VanSweden, LEED AP, integrative designer at the environmental consultant firm Catalyst Partners in Grand Rapids, and Vince Novak, AIA, managing principal architect at TSK Architects of Grand Rapids, spoke at the event and noted modern solutions for reducing the impact of embodied carbon can begin before materials even reach a project site.

“Every material we see in this room came from somewhere else,” VanSweden said at the beginning of the discussion. “What that means is to get into this room there was a process. It had to be extracted; it had to be transported to the manufacturing facility, but then also to the job site. It had to be built and put together and then it has to go somewhere when it’s done.”

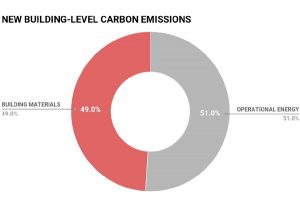

The operational and building phases of a building’s lifecycle create nearly equal amounts of carbon emissions, according to VanSweden; though the operational phase often targets energy efficiency or reducing the use of fossil fuels. In reality, it only comprises a structure’s middle ages, and mitigating waste at the end of a building’s lifecycle involves a considerable amount of carbon, as does the initial effort of getting materials to a project site.

To reduce these first traces of embodied carbon, Novak first suggested recycling materials like timber, concrete, and steel since they’ve already been extracted, manufactured, and processed. Otherwise, carbon levels and building costs can be lowered by using less high-carbon materials like aluminum and copper, and increasing the use of regionally-sourced, low-carbon alternatives like fly ash and lime cement blends or mixtures of compacted earth.

To reduce these first traces of embodied carbon, Novak first suggested recycling materials like timber, concrete, and steel since they’ve already been extracted, manufactured, and processed. Otherwise, carbon levels and building costs can be lowered by using less high-carbon materials like aluminum and copper, and increasing the use of regionally-sourced, low-carbon alternatives like fly ash and lime cement blends or mixtures of compacted earth.

“[These are] examples that aren’t used a lot but those are the things I think we have to start thinking about,” Novak said. “Why are we using what we’re using in construction?”

The speakers also discussed solutions like carbon-sequestering topography or green roofs, and initially designing buildings to be regenerative at the end of their lifecycles.

In the end, they explained that the simplest way to reduce carbon emissions—and cost—is to utilize pre-existing structures when possible; and to plan early, with goals for sustainability underlying the overall process.

“At the beginning of the process you have the ability to have the most impact for the least cost,” VanSweden said. “As you get more definition and more documents and more artifacts in the design process, the cost to change the project is significantly increased and the amount of impact you can have is significantly decreased.”

Catalyst Partners helps its clients achieve their sustainability goals early by providing services like daylight simulation and energy modeling among a variety of others. The firm takes a collaborative approach to transforming local businesses and institutions into celebrated examples of sustainability. Near its Grand Rapids headquarters, the firm’s work is seen in a variety of Grand Valley State University buildings as well as Brewery Vivant, the first LEED Silver-certified production brewery in the country.

A more recent addition to the city’s portfolio of architectural and design practices, TSK Architects has also been a proponent for sustainable building and design. In 2006, its own studio in Henderson, Nevada was recognized as the first LEED-certified building in the state, and many projects in the firm’s range—which spans civic and justice complex design to higher education—follow suit.

Along with the USGBCWM, both firms are part of an understated, city-wide movement to improve structural sustainability and the region’s future quality of life. The USGBCWM will host another event in September 2019 to address carbon emissions on a global scale. The conference, Rise Up & Draw Down Michigan, will feature keynote speaker Paul Hawken, the editor of the New York Times bestselling book “Drawdown: The Most Comprehensive Plan Ever Proposed to Reduce Global Warming.” The event will aim to create optimistic discussion around local solutions for the worldwide force of global warming.

Text: R. Collins | GLBD writer

Photography: USGBCWM