In 1823, a Baltimore-based businessman ran an advertisement for the sale of a Wire and Wheat Fan Establishment in the “The American Farmer: containing Original Essays and Selections on Rural Economy and Internal Improvement with Illustrative Engravings and the Prices Current of Country Produce, Vol. IV.” In it, J. Grafflin listed the sale of wheat fans, rolling screens, and “assorted wove wire for windows and other purposes,” and R. Sinclair, who purchased the establishment, indicated he intended to keep the “ready-made, all kinds of wove wire, suitable for rolling screens, safes, riddles, sieves, and wheat fans.”

While other entrepreneurs and inventors would quickly sell, advertise, and file patents—such as Bayley & McCluskey in 1868 for car ventilators in rail-car windows and E.T. Barnum Company of Detroit’s notice of selling screens by the square foot in 1874—it was this publication, The American Farmer edited by John S. Skinner and published in Baltimore, that held one of the earliest mentions of what has now become an international household staple: the window screen. In 1881, J. Koch would file another patent—No. 246,153—for the “Window Screen” and set a standard for screen design for years to come.

Though the industry would adapt and change in the coming decades, much of what constituted as a window screen in the late 1800s remained the same into the 21st century, until a Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania-based entrepreneur, inventor, and former sales representative in the window screen industry took to his garage to solve the nearly century-old problems facing traditional screen technology.

“I’ve been in the window and door industry for about 20 years and for most of that I was an independent sales rep, so I sold pieces and parts to window manufacturers like glass, hardware, and silicone—things they needed to make a window—and one of the things I sold the most was window screens,” said Joe Altieri, third-generation entrepreneur and chief executive officer of FlexScreen LLC in Pittsburgh.

“I was pretty good at selling screens, but as we sold more and more, what became evident with my customers and ultimately the homeowners, is they had a lot of problems with window screens to the point where it is about three-to-five percent of the screens produced in North America have to be repaired or replaced before the homeowner is happy,” Altieri added.

The traditional window screen is often manufactured out of painted aluminum and while there have been improvements in durability to the material, Altieri noted the material can still be fragile, the hardware can be complicated, and the screen itself often impedes on the view through the window. With a goal in mind to create an entirely new frame design that was flexible, durable, and didn’t require installation hardware, Altieri set out on a three-year, labor-of-love endeavor testing different materials and products from plastics and fiberglass to steel.

“I would walk down the aisles of Lowe’s, Home Depot, and others, and go: ‘Can I make a screen out of that?’” Altieri said. “I tried to come at it from different directions.”

In the end, Altieri said inspiration for the frame’s core material came from watching an electrician use a narrow band of spring steel, otherwise known as fish tape, to route wiring at his home office. Upon purchasing six steel fish tapes, Altieri fashioned a flexible frame prototype that would ultimately become known as the signature product in FlexScreen LLC’s portfolio.

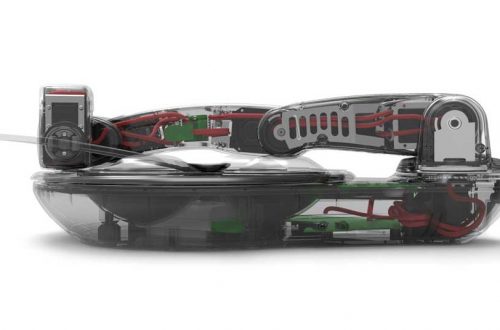

Simple in design, FlexScreen features a core of phosphate-enhanced, high-carbon, oil-tempered spring steel that is then sprayed with an exterior-grade, high-performance duralloy PVC coating, adhering the mesh to the frame. The high-carbon, oil-tempered spring steel is often used in garage doors and automotive leaf springs and is a high-tensile, durable, and malleable material. Altieri also noted one of the added benefits of the substrate material is its ability to collapse or compress and then return to its original form, resulting in ease of installation.

“We’ve run them over with cars, we’ve thrown them off buildings, we do all kinds of crazy things to show how resistant to damage our frame is, so that was the big push for the oil-tempered spring steel. Then, as we were looking at how does someone put it in and out, because it is not the same as a regular screen, one of the take-offs of using spring steel was that it is flexible,” Altieri said. “When you press in the middle, the sides will collapse in, and you can grab it and take it out really easily.”

Today, the nationally and internationally patented design is a flexible, durable, and scalable product available in both full- and half-screen measurements featuring decorative, snap-on pieces to match window frames. From 96-inch-tall screens for door sidelights with crank, casement type frames to commercial-sized windows, Altieri noted fondly the company has the “one-screen-to-rule-them-all” when it comes to dimensions.

“Our screens work both commercial and residential, so we do have full screens and half screens, but our main product is the FlexScreen full screen that covers the entire opening of the window. There are certain segments [in the window industry] who prefer half screens, so we do half screens and there is a little decorative piece that snaps onto it,” Altieri said.

“One of the benefits from the design side is that our screens disappear. You don’t seem them anymore and so we wanted to make sure even with the half screen that was still the case, that a homeowner taking a step back from their windows, the screen is still gone from their view,” Altieri added.

Designed to insert into window screen tracks to hide its frame, FlexScreen’s minimalist design enhances rather than detracts or distracts from the view through the window itself, especially as industry trends for larger expanses of glass continues. Altieri noted regular screens often impede on the view due to thicker measurements around the frame and the fact that FlexScreen is meant to hide in a pocket designed for the screen in the window is something the team explains to customers and homeowners.

“If you take a standard window and you do three-quarters-of-an-inch all the way around it, it’s over a square-foot of view,” Altieri said. “It is the simplicity of a product that makes great design and as far as a window screen goes, you can’t get simpler than ours. We have the mesh that blocks the bugs, the frame that makes that mesh nice and tight, and we get it out of the homeowners’ view so they don’t even notice it anymore.”

Since opening its first 44,000-square-foot facility in Pittsburgh to serve the western Pennsylvania, West Virginia, Ohio, and eastern Michigan region in 2014, FlexScreen has not only grown its manufacturing footprint to encompass locations in Vermillion, South Dakota; Atlanta, Georgia; and Ontario; but also expanded its online retail presence with a recent strategic partnership with Saint-Gobain ADFORS. The latter is a leading international manufacturer of high-performance construction and industrial materials, and through the partnership, has retained rights to sell FlexSreen products. FlexScreen has also obtained a patent in Hong Kong and finalized an equity partnership valued at approximately $800,000 with “Shark Tank” Entrepreneur and Investor Lori Greiner.

“Design is all about beauty and simplicity. It is about trying to make things beautiful, but also trying to keep them as simple as we possibly can,” Altieri said.

Full text available in Great Lakes By Design: Ergonomics, 2021.

Text: R.J. Weick

Photography: FlexScreen LLC