The Great Lakes ecoregion has stood witness to the passage of time as marsh, dune, and forest habitats expanded and contracted, economic engines of industry rose and fell, and the growth of city populations surged and declined in cyclic fashion. While stalwart, its composition of freshwater sand dunes, sandstone cliffs, pebble beaches, limestone bedrock, and wetland basins have felt that impact as aquatic and shoreline habitats either were encroached by pollution or became hardened and armored coastline to combat issues like erosion.

With a total surface area of roughly 94,600 square-miles, the Superior, Huron, Michigan, Erie, and Ontario interconnected waterways is the largest freshwater system in the world. It is a historic, cultural, ecological, economic, and recreational hub home to more than 3,500 species of plants and animals, a wide variety of climate, soil, and topography, and serves as the backbone for a $6 trillion regional economy. It is the source of drinking water for more than 40 million people in the U.S. and Canada, and recreation alone generates more than $52 billion annually for the region.

While a restoration of the region’s most valuable and, in the hearts of many who call it home, precious natural asset to pre-settlement conditions is near impossible, a healthy lake system is critical not only to the local environment, but also its communities. And in Euclid, Ohio, an unprecedented, public-private model may prove transformative to the region for comprehensive waterfront stabilization, one that invests in the people and the connection they have with the shoreline and its waters.

“When we think about investments along waterfronts, they have to do so many things. They have to function from an ecological perspective, they have to function from a recreational perspective, and they have to support this moment where you look out over the lake and it moves the human spirit, where you are like, ‘that is beautiful.’ It has to accomplish so many more things and I think that realization is becoming more pervasive throughout design, whether it is along shorelines or in how we look at roads,” said Jason Stangland, PLA, LEED AP, principal landscape architect and Waterfront Practice Director at SmithGroup in Madison, Wisconsin.

“I think infrastructure investments that really organize themselves around achieving multiple goods are where the world is headed and I think Euclid starts to change that paradigm and push that forward in the Great Lakes,” Stangland added.

SmithGroup is an award-winning, global, integrated design firm focused on developing sustainable, beautiful, and future-focused solutions across disciplines in the built and natural environments. With 170 years of experience and a network of 19 offices in the United States and China, SmithGroup is on a mission to design a better future, working with partners and clients to deliver well-designed spaces, places, and processes. Throughout the years, the firm has become recognized for its waterfront planning and design, developing comprehensive and integrated, resilient solutions that are intended to heal, restore, and protect water-based landscapes while reestablishing them as part of the urban and social fabric. Backed by a team of engineers, ecologists, landscape architects, and urban design experts, SmithGroup’s Waterfront Practice specializes in coastal habitat protection and restoration, green infrastructure, living shorelines, and navigating the complexities of river, lake, and ocean environments. Throughout the years, the firm has worked on waterfront projects like the Blue Water River Walk in Port Huron, Michigan; Ocean Reef Islands and Marina in Panama City, Panama; the Milliken State Park and Harbor in Detroit, Michigan; the Kinnickinnic River Corridor Neighborhood Plan in Milwaukee, Wisconsin; and the Ayia Napa Marina in Nicosia, Cyprus.

For Euclid, whose city boundaries stretch nearly four miles along the Lake Erie shoreline, its lakefront remained largely inaccessible to the public and had experienced severe bluff erosion, loss of nearshore habitat, and posed threats to adjacent development, privately owned properties, and homes. In 2008, the City of Euclid looked to SmithGroup to help change that narrative, initially interested in a feasibility study for a recreational marina and additional shoreline access to Lake Erie for the public just east of Sims Park. Stangland noted one of the initial challenges was addressing how to build structures to protect boats and development of that nature across city-owned and private-owned property, while taking into account technical issues like longshore movement of sand.

“We were asked to initially look at a market study for a recreational marina and as we started to move toward developing that concept, we started engaging with the landowners and the residents. There were a lot of concerns about not just having a recreational marina proximate to them, but more so they were concerned about equitable access to the lakefront and making sure that they wouldn’t lose their access, or that we would expand access or that their shoreline is crumbling and eroding,” Stangland said.

“That was the motivating factor for folks to come to the table and they started with the understanding that, ‘okay, we can do all these things if we collaborate and work together.’ And that is how the project evolved from an initial recreational marina study to a comprehensive waterfront strategy for a three-quarter-mile-long shoreline,” Stangland added.

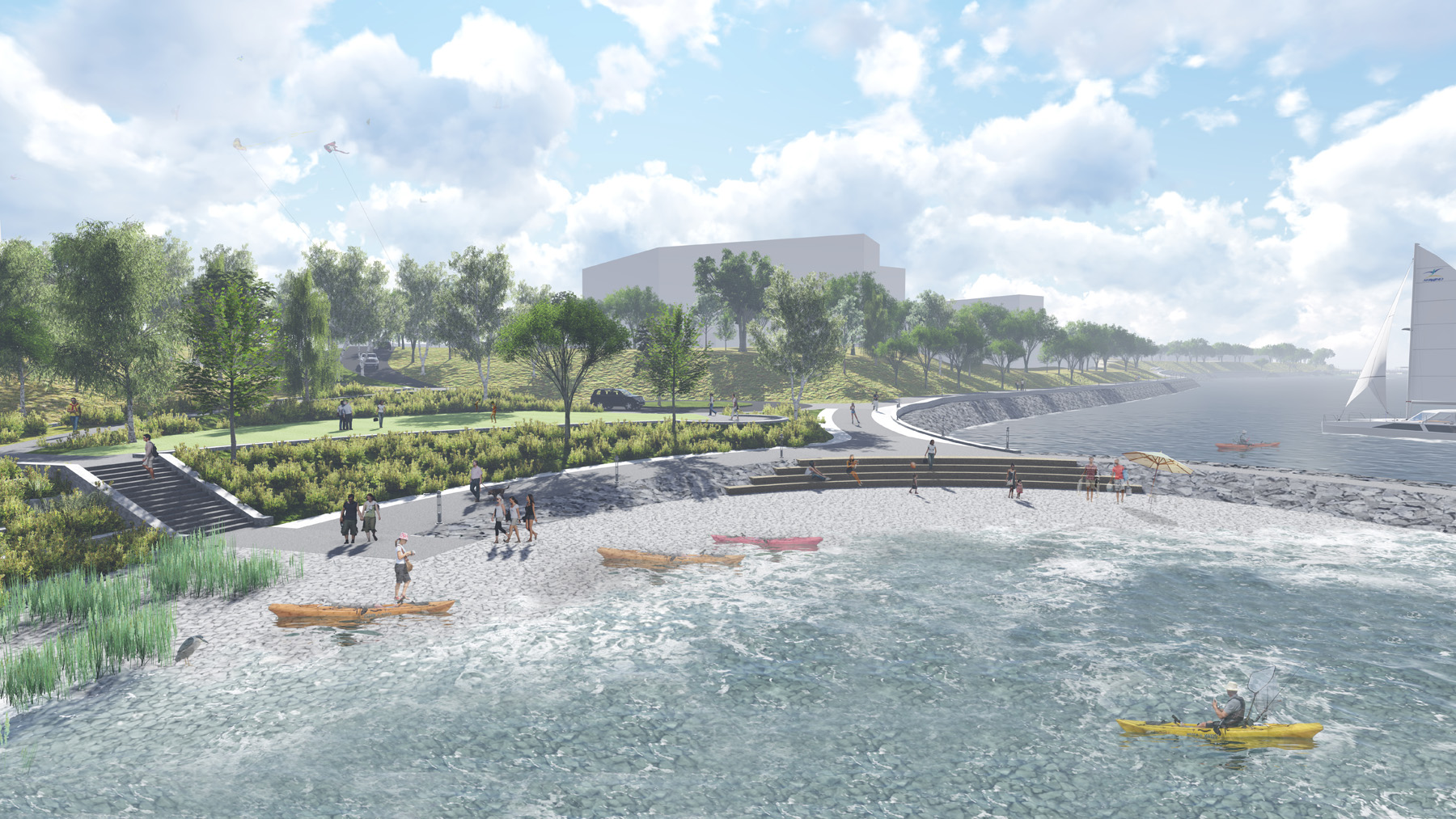

Due to the size of the identified shoreline for the project and the combination of public and private land ownership, SmithGroup led extensive public outreach and engagement, meeting with individual homeowners, business owners, private developers, and public officials. The team also worked with politicians, state and federal regulatory agencies, and grant staff to begin developing a comprehensive waterfront improvement plan that would benefit all stakeholders in the community and the ecological watershed. Through this process, a holistic vision integrating habitat, erosion protection, beach creation, bluff stabilization, and the creation of a continuous public access corridor at the water’s edge began to take shape.

In 2013, the Joseph Farrell Memorial Fishing Pier in Sims Park served as the catalyst and key milestone for the community as years of planning became a built reality as Phase I of the Euclid Waterfront Improvements Plan. Designed to provide universally accessible fishing to deeper water, access to the pier’s lower platform, and as a connector to area park trail systems, the 200-foot-long Sims Park Fishing Pier and its sculptural, arched shade structure also served as a gateway to the future trail that would eventually be developed.

“It was wildly successful just with people coming there are all times of the day and night, and that was a really important moment. I remember during the grand opening, one of the residents walking up to us and talking to us about it and they said, ‘you know, I invested in the right place, because Euclid invested in me,’ which was the first time I heard somebody say something like that to me,” Stangland said. “It’s pretty impactful that an investment in recreational infrastructure and improvements is seen that way as such an economic investment.”

The Euclid Waterfront Improvements Plan also comprises a Phase II in which shoreline stabilization and the creation of a multi-purpose trail and boardwalk would enhance both habitat and public access, and a Phase III that includes the development of a public marina. In 2018, Euclid’s City Council voted to approve the unique public-private collaboration in order to move forward with Phase II, which is currently nearing completion. But to execute it, SmithGroup had to first work with the City of Euclid to either acquire or develop easements and agreements with owners of nearly 95 percent of the project’s waterfront shoreline. While four properties were acquired through grant funding and an additional two were donated, the team also worked to secure easements with two developers, five individual owners, and two beach clubs with over 70 total residences.

“What I think is probably the most compelling element is really that a bunch of landowners decided they were going to come together and work with the public to get public access. Who does that? It has been an amazing thing to watch and more so than anything—the aesthetic could be pink, purple, polka dot, it doesn’t really matter—what people care about is providing access and addressing issues like shoreline erosion,” Stangland said.

“That model, which has loosely become known as the Euclid model, became something that is being replicated throughout the entire county, because Euclid did something so unique. I think more so than anything that is really the legacy of this project,” Stangland added.

For Phase II, SmithGroup leveraged a series of coastal engineering techniques to enhance the shoreline, such as aligning hardscape features at the waterfront to control movement of sediment in the littoral zone, introduced strategic nearshore and offshore breakwater structures, varied sediment and cobble substrates to stabilize and improve habitat, and neutralized downdrift impacts and stabilized bluffs through the formation of prefilled sequential pocket and feeder beaches. Stangland noted everyone is inherently linked along the lakes and designing solutions for the stretch of waterfront requires an understanding of the broader contextual dynamics of how shoreline processes work.

“Investments in infrastructure like wastewater treatment plants and things like that all change the dynamics of shorelines, so it is not so much about exactly the shoreline we are dealing with as it is the context. How sand moves along the shoreline for example was one of the critical components to that. They used to have a very wide beach there, about 150-to-200 feet that disappeared over a 19-year period. That created a tremendous amount of exposure to larger waves and ice shove,” Stangland said. “It really started to degrade the shoreline rapidly. You went from these wide beaches to these really vertical bluffs.”

The bluff, at nearly 30-to-40 feet tall, can then respond very quickly to erosion where physical changes can then be seen in a matter of months, especially considering the record high water levels in the Great Lakes and the wave activity experienced during Hurricane Sandy. To design a resilient solution, the team first numerically analyzed sediment drift patterns and wave focusing using fine scale wave transformation modeling to establish a tentative shoreline geometry. Then, it underwent testing in a physical model to refine the shape, structural location, and alignment for aesthetic and functional performance.

“It always starts with technical studies of wind, wave, and ice, but it actually looks at things like the bathymetry, which is the lake bed contour and that has a direct implication on how waves interact with the shoreline or how they turn and respond to the shoreline and how big a wave can actually grow,” Stangland said.

“We did some upfront analyses and we actually did a physical model, which is like a big soccer field bathtub and we basically built the whole shoreline with proposed improvements at one-twenty-seventh, half-inch scale just to test how the waves would interact with the shoreline,” Stangland added.

The team also tested different scenarios in terms of water levels, wind direction, wave directions, and storm activity—like the 17-to-20-foot-tall waves witnessed out of the northeast in Lake Erie from Hurricane Sandy—to optimize the structural design. Stangland also noted as part of the process, the team ended up removing around 22,000 tons of concrete rubble, steel, and debris—including a derelict boat stranded after being punctured by submerged debris—from the stretch of shoreline from permitted and unpermitted fill previously placed along individual properties to serve as makeshift shoreline reinforcement.

Visually, the western-most section of the waterfront features cobble beaches and as the trail heads eastward to the pier, it goes through a series of strategic pocket beaches and breakwaters before transitioning into more conventional revetment where the planned recreational marina is anticipated to be built. Stangland noted another compelling element of the project has been in walking the shoreline with visitors and hearing their impression of the cobble beach and other design elements, thinking they have always been there.

“It is neat to see people’s reaction and I think there is enough natural components to it, the cobble beaches are unique enough in terms of the solution and approach, that people respond to it. It fits. I think trying to push the boundaries on what shoreline protection looks like—and this [public-private] model—are two pretty compelling aspects of this project to me at least,” Stangland said.

While the ambitious, multi-phased plan is still underway, it was recognized in 2021 by the Ohio Economic Development Association during its Annual Award Excellence Awards with a Best Project Award, celebrating its achievement in economic and workforce development. Stangland noted though it is impossible to go back to the natural processes that once existed on the Great Lakes, it is important to be able to use creative design and engineering to solve problems within the changing dynamics and context of today’s reality on the waterfront. And it is also about bringing in collaborative input beyond the team like in Euclid, where stakeholders across the community and design team can relate to what is beautiful and what is recreationally valuable to them.

“Design is such a collaborative process. Design is a team sport more than anything and I feel like the team sport is often thought about as a black-caped designer or somebody who has this extraordinary knowledge and aptitude, but when you pull back the Wizard-of-Oz-like curtain, it is just normal people solving problems creatively, but the creative part of the process is actually driven by input from all of the people,” Stangland said.

“It is not about creating an icon, it needs to be something that functions for the people who use it and everything else. I think beauty in design is really achieved through that collaborative process and solving problems. I think there is a stark difference when you look at a conventional revetment versus a cobble beach or you look at standard conventional engineering versus design,” Stangland added.

First published in Great Lakes By Design: Raising the Bar, 2023

Text: R.J. Weick

Photography: SmithGroup, Plum City Photo