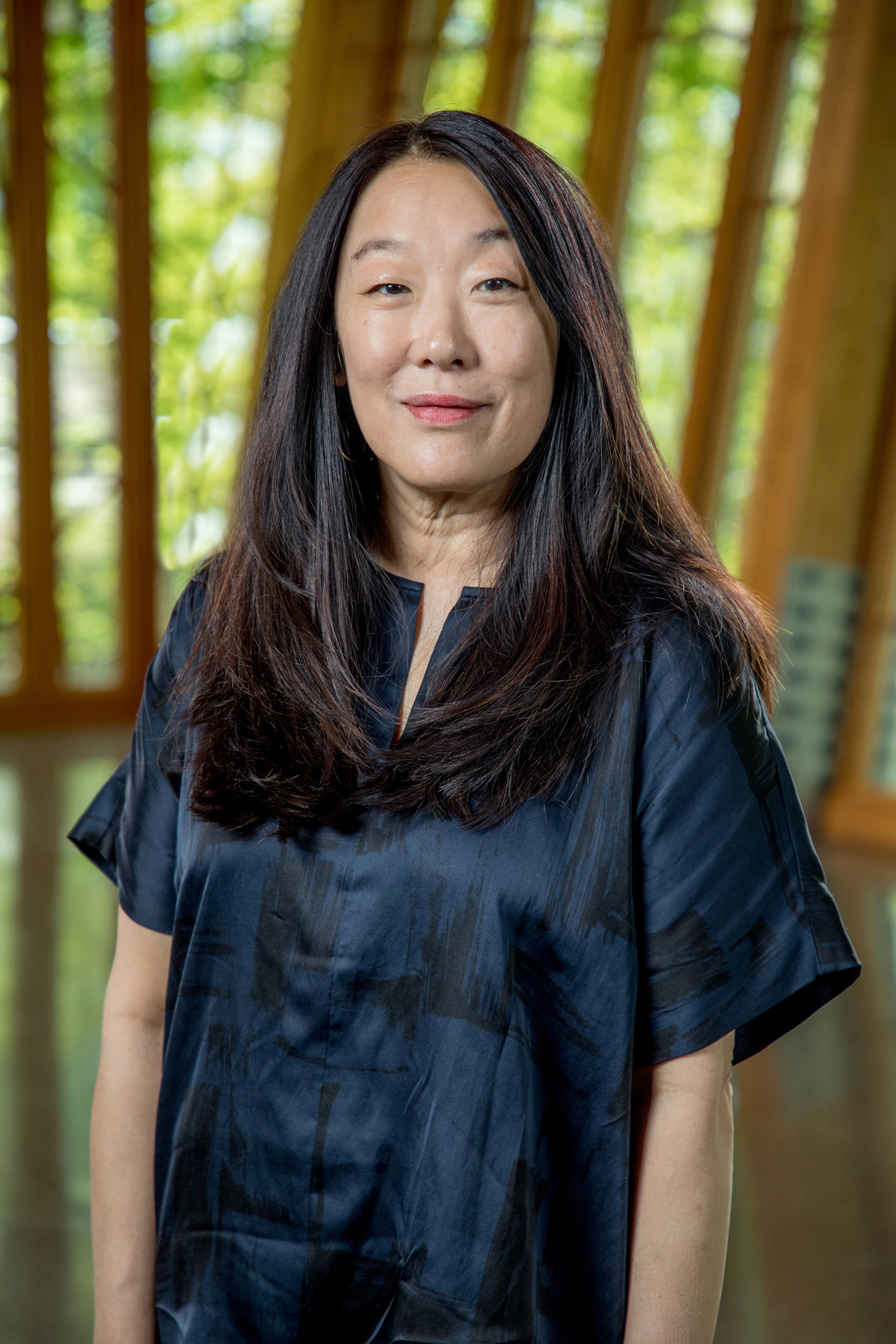

Founder, Owner, Principal

KOO | Chicago, Illinois

In architecture, as in literature, arts, and other social sciences, there is a wealth of traditions, movements, applications, and analyses—avant-garde, thought-provoking, and otherwise—that have shaped their respective fields throughout time and have challenged scholars and practitioners alike to consider the world and communication around them anew. For many, architecture is a form of communication, a language written through form, function, and material—and for the deconstructivist, the exploration of tension and potential contradiction.

For Jackie Koo, AIA, IIDA, LEED AP, NOMA, founder, owner, and principal of KOO in Chicago, Illinois, it was the combination of philosophy and the examination of architecture that first drew her to the field at a time when deconstructivism was hitting its stride through form-defying non-rectilinear shapes and the presentation of exhibits, such as the “Deconstructivist Architecture” exhibition in 1988 at The Museum of Modern Art in New York. Though initially interested in becoming an architectural critic, writer, or philosopher, Koo said she quickly fell in love with the process of designing and seeing work built.

“I found that ultimately to be much more rewarding, so while I went into architecture with the intention of going in a more academic direction and maybe doing more conceptual-type projects, exhibits, or critiques, I ended up firmly in the practitioner’s role,” Koo said.

“I was actually a philosophy major as an undergrad. After that, I tried a couple of other career paths—I was a photography assistant, then I was in retail advertising—but I realized it wasn’t a long-term career for me in terms of satisfaction and so I went back to what I had gone to school for, and went into architecture with the intent of becoming an architectural critic or historian or something like that,” Koo added.

Informed by her studies in philosophy at the University of Chicago, where she earned a Bachelor of Arts, Koo went on to attend the University of Illinois at Chicago’s School of Architecture for a Master of Architecture degree. Koo noted when she went back to architecture school, it was during the era of deconstructivism, which, not unlike deconstruction in literature, deconstructs meanings.

“The design process endeavors to eliminate the author or authorship and that does have somewhat of an influence on me today, because the way that I run my practice, too, is not like the heroic architect of the past, the single author. We have a very collaborative office environment in which the designs come out of a group charrette process. Everyone can be involved in generating ideas, then pursuing maybe four of those ideas and drilling down and experimenting with those,” Koo said.

“It’s a very different process from what a lot of people perceive architects to be. In the fantasy world of architecture, there is a single person creating a design from a hand sketch, but if you are working at a larger scale, the projects are drawn by large teams of people. It is not just one person who executes a project like the hotel at Navy Pier. Almost the whole staff worked on making that project come together,” Koo added.

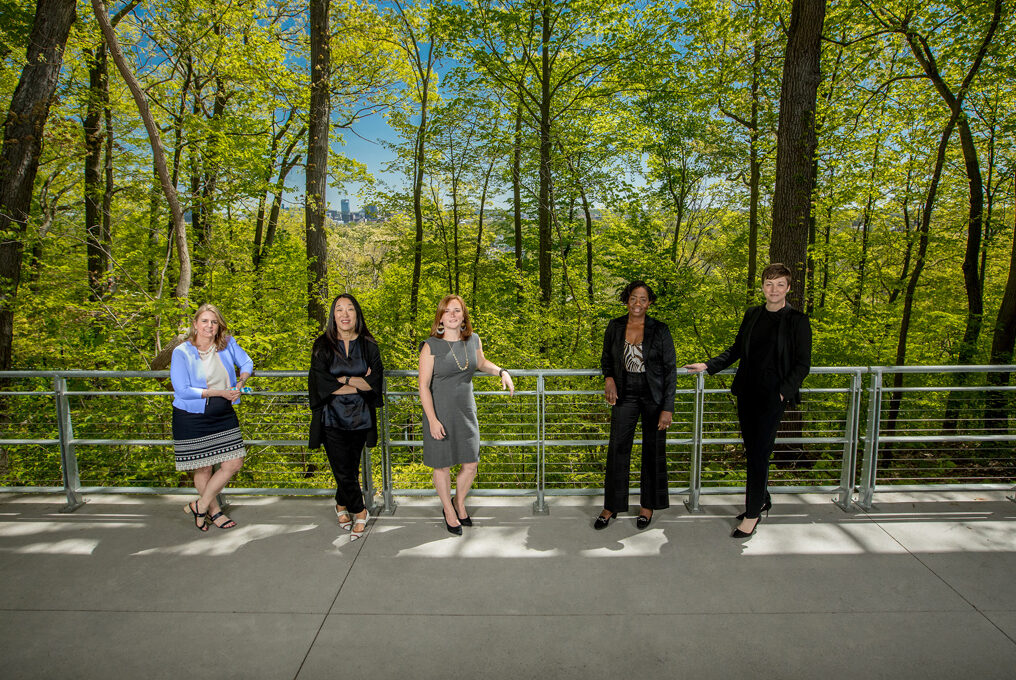

KOO is a full-service architecture, interior design, and urban planning firm based in Chicago. It is also a certified Minority Business Enterprise, Women’s Business Enterprise, Disadvantaged Business Enterprise, United States Green Building Council member, and a signatory to the AIA 2030 Commitment. Since its establishment in 2005, KOO has developed a portfolio that embraces the new and temporal, while still being informed by the technical. The studio of talented architects and interior designers is led by Koo, and as a team, strives to create a visual narrative for each project that reflects the unique identity of its clients, community, and context.

“We have a very open design process in the office, one of trying things and experimenting with ideas. I like to try to include something that reflects the identity of the project in a meaningful way that people can understand. We are always trying to create moments where the users will feel inspired by design,” Koo said.

“I believe in the value of design to elevate the human experience and then aesthetically, I would say—and this is more my personal bent rather than necessarily the way the design in the office always goes—I am interested in the legibility of design. Rather than having an artful randomness that you see so often in architectural patterning and design these days, I like to be able to understand something, what it is. I find that very gratifying,” Koo added.

The studio’s work has touched on a diverse range of typologies and scales across hospitality, educational, civic, residential, urban design, renovation and adaptive reuse, sustainability, and preservation sectors, that has led to innovative projects such as the esports and virtual reality arena on the boards now; a mixed-use 40,000-square-foot library, childcare, and community center known as the Altgeld Family Resource Center in the heart of a public housing development, Altgeld Gardens; and the Sable Hotel at Navy Pier, part of the Curio Collection by Hilton; and Offshore, a “World’s Largest Rooftop Lounge,” according to the Guinness Book of World Records. A large part of Koo’s practice focuses on municipal and civic work for various city agencies like the Chicago Housing Authority, Chicago Public Schools, and the General Services Administration.

“It’s actually my favorite thing about the practice, being able to work on such different typologies. As architects, if you are lucky, you can learn about something new or someplace new all the time. I think that is one of the most rewarding aspects about what we do; it’s a new problem every day on every project and we try to approach each project with the idea that it has something to teach us,” Koo said.

“The hotel on Navy Pier, for example, was totally different from doing a hotel in the Loop downtown. That is what is great about our practice; the challenges you face are very different and the response that you create is very different as well. But we are also so lucky to be able to try new typologies like the esports stadium we are working on now, and nobody has done too many of those, so we get a chance to learn something totally new,” Koo added.

Though now recognized for its distinctive and award-winning work, Koo said she didn’t start out her architectural career with her own firm, but rather spent nearly 15 years working for a variety of corporate firms. By the time she looked to launch her own endeavor, Koo said she was in her 40s and had been running multiple jobs and teams, managing profitability among other aspects.

“What allowed me to start my own firm was building enough experience to gain confidence. A lot of architects start very young, but I don’t think I had the confidence and then, another inspirational thing for me, was that while I was at my last corporate firm, I was managing three, women-owned and minority-owned architectural firms, smaller ones,” Koo said. “They were led by women of color and it put the thought in my head that this was something I could do.”

From apartment-based startup to the robust architecture, interiors, and planning firm it has become today, Koo credits KOO’s debut project—theWit, a roughly 250,000-square-foot, 300-key hotel—as a critical point in the studio’s journey. theWit, which is a boutique-branded, Hilton hotel set on the northern edge of Chicago’s Theater District and State Street, featured a 27-story, chartreuse glass “lightning bolt” zigzagging up the building.

“It is kind of unusual to have a 27-story building as your first constructed project when you start your own firm and that set me on a path of being much more adventurous with design than I probably would have been otherwise,” Koo said. “It allowed me a freedom I probably wouldn’t have had otherwise.”

Initially known as Koo & Associates, Koo has since rebranded the studio as KOO to reflect the shift in identity from a more corporate direction—which had influenced her earlier career—to something more personal and experimental in nature. For those inspired by or pursuing the field, Koo noted it is a good idea to try a lot of different project types and tasks, and try to avoid being pigeonholed, especially in the beginning.

“Ultimately, it is a way to discover who you are and it is the same advice I would give to my son,” Koo said. “You should be patient and get to know yourself and what your strengths are. Ultimately, even if architecture, in the traditional form of practice, is not the direction you want to go, because it is not for everyone, design-thinking is a very valuable tool and a great foundation for life—and lots of jobs.”

Koo also noted she would love to see a greater understanding about the value of design and how it can be life-changing for people rather than being so often viewed as a commodity, and the critical issues facing architecture today are the same ones that society is confronting.

“Equity, sustainability, resilience: I think architects have huge contributions that we can make,” Koo said. “From an equity standpoint, there are few women in the C-suite as compared to the number of women in architecture or in the population generally, and diversity from a racial level is even worse. The statistics are pretty astounding.”

Having more women, and more women in positions of leadership in the field, Koo noted it is not only fair, but also leads to innovation by giving diverse perspectives in design and the culture of architecture, which historically has been male-dominated probably because it is a construction-related industry.

“There is a history of architecture being inaccessible to a lot of people and having role models is so important. I think that unless you can see somebody like you doing it, you can’t necessarily see yourself in it,” Koo said. “In the same way that when I started my own practice, a big part of it was I could see myself in these other firm owners and in that position.”

While Koo also sees another challenge as the general misconception of what architects do and how that has changed over time, it is about making sure the work is understood and conveying that value of design—and its relevance—to the audience or users.

“Design is my lens for understanding the world and contributing to it,” Koo said. “When I go through life, I view everything with that design lens and it is just so rewarding and meaningful to be able to be a part of that discussion.”

First published in Great Lakes By Design: Architectonics, 2021

Text: R.J. Weick

Photography: (profile) M-Buck Studio LLC

Selected KOO projects:

Photography: (gallery) Mike Schwartz Photography, Anthony Tahlier Photography

2021 Architects