In Core City, Detroit, urbanism is defined in unconventional terms. For the creative and technical minds behind the neighborhood development at the intersection of Grand River Ave. and Warren Ave., it is about investing in intentional and thoughtful ideas grounded in reality to create a place rather than a market or projects motivated by demand. It is about renovating and activating land that has been vacant for decades in a manner that not only honors the history, people, and space characteristic of the surrounding city, but also enhances and preserves the environment through developing as little real estate as possible.

Core City envisions a depopulated urbanism, where public spaces like gardens and parks are subsidized by compelling small-to-medium scale sensitive development projects that bridge culture and community, and nature and structures, to create a novel destination for people to live, work, and have meaningful connections.

“In my philosophy of real estate development, I am kind of an alternative developer in that most developers try to preserve as much space for themselves and sell the least amount of space for the highest price they possibly can, whereas I say space is actually what I make,” said Philip Kafka, president of Prince Concepts in Core City, Detroit. “That is my product and if I can figure out how to give people more space for a comparable cost that they would pay for less space, then I’m really good at what I do.”

Prince Concepts is a real estate development and property management company that prioritizes space, often employing utilitarian methods to develop lower-density areas that designate the majority of resources to high-quality public and private spaces. Under the direction of Kafka, Prince Concepts and its team of professionals has worked with local architects, designers, builders, landscapers, and creatives since 2012 to realize unique projects within 17 acres of land and has been recognized both nationally and internationally for their work. In 2019, Prince Concepts in collaboration with Julie Bargmann of D.I.R.T. Studio, transformed a 10,000-square-foot site with an 8,000-square-foot public square and neighborhood space featuring 87 trees in a former parking lot known as Core City Park. The following year, in collaboration with UNDECORATED and Iannuzzi Architecture Studio PLLC, the collaborative completed the conversion of a 13,500-square-foot former grocery store into a build-to-suite commercial space known as 5K, designating nearly 17,000 square-feet remaining onsite for landscaped programming.

It was, however, the 10-unit, live-work community project known as True North that would serve as the catalyst for the overall development and its most recent addition to the Core City initiative known as The Caterpillar. True North, initially completed in 2017 with design by Edwin Chan, founder and creative director of EC3 in Los Angeles, and architecture by Studio Detroit in Detroit, reimagined the use of the Quonset hut as a flexible and dynamic residential and commercial space for the modern century. Four years later, The Caterpillar builds on the sculptural community True North established with a new eight-unit, single silhouette inspired by a UFO crash landing in a forest, the Pompidou Museum in Paris, and the pastoral landscape of the Midwest.

Inspired by the essence of True North, The Caterpillar intended to address some of the construction difficulties presented while building inwalls of the live-work community. Kafka noted it sought to build upon the earlier project, reinvesting cost savings in the quality of spaces for the residents and the landscape for the neighborhood—while being more efficient with the structural material and working within zoning constraints.

“True North was successful. It was culturally successful—it really kickstarted the neighborhood—it was financially successful—we achieved rents that were higher than we anticipated—and it was aesthetically successful—we received at least three really prestigious architectural awards that I was very proud of and so I wanted to use the lessons I learned from True North in terms of how to culturally activate a place, how to make a place more beautiful, and also how to succeed with a project as a real estate developer—and I wanted to use the Quonset hut,” Kafka said.

“Even though it is a utilitarian structure, it still requires some figuring out and we made some mistakes in how we designed our first project, because we didn’t really know the medium that well and so as we got to know the medium, ideas came to me and that is when I challenged Ish [Rafiuddin],” Kafka added.

Longtime collaborative partner, Ishtiaq Rafiuddin has left his architectural design mark on projects across the globe in previous roles such as project designer with REX Architecture and OMA of New York City, partner with MIMAJ in Istanbul, managing partner of Based In of New York, before launching UNDECORATED in 2017. Now serving as principal and creative director of a five-person team in Detroit, Rafiuddin said The Caterpillar happened to be one in a sequence of projects the team hopes to do together to revitalize the Core City neighborhood.

“In [True North], they used Quonset huts, but in that case one Quonset hut typically equaled one unit. I was familiar with the project, because I was, at the time, working on projects in the neighborhood, so it was something we were familiar with as a tool. We see it as a tool for constructing, and in the case of Caterpillar, the goal was to do all eight units in one hut,” Rafiuddin said.

“In the development world, it is not something that is typically used and I believe it is because when you use it, you are saying you want to operate on the ground level. We already had that philosophy, because we love land so much. We said, ‘hey, we really want to connect with the land and we do want to be on the ground level,’ so the Quonset hut made a lot of sense. We didn’t need to build up and have multiple floors,” Rafiuddin added.

The Quonset hut is a lightweight, prefabricated structure typically comprised of corrugated, galvanized steel and semi-cylindrical in form. Initially developed by the United States Navy in the 1940s during World War II, the Quonset hut was inspired by the Nissen hut patented in 1916 by Major Peter Norman Nissen of the 29th Company Royal Engineers of the British Army during World War I. As a flexible, all-purpose and lightweight building solution commonly 20-by-48-square-feet in dimension, the Quonset hut’s 960 square-feet of useable floor space was leveraged for a number of uses from barracks and latrines to medical space during WWII. After the war, the military offered its surplus to the public and has since been used for outbuildings, storage space, farming operations, businesses, and homes.

For Rafiuddin, who noted one of the amazing things about being in the Midwest coming from New York—a place of congestion and a lot of density—is the prevalence of beauty and open space, the urban-pastoral landscape of Detroit lent itself well to the Quonset hut materiality and the landscape-focused element of The Caterpillar project.

“There is nothing like it, I think, in America where you have an urban grid and at the same time you have this feeling that you are in the countryside. We are really inspired by this and I think for us the goal is, if we are going to do development and architecture in Detroit, you want to be very specific to its condition and so the precedent for it is how do we take on the challenge and how do we present it with architecture that is fitting?” Rafiuddin said.

“At the same time, Detroit obviously has had a very interesting history. It was one of the wealthiest places in the world at one point and it was basically the center of technology for decades and in more recent history, there was disinvestment in the city that has led to people leaving. We also want to reflect that in the architecture in the sense that whatever we propose, we want it to reflect the urbanism and the history, but at the same time not be out of place,” Rafiuddin added.

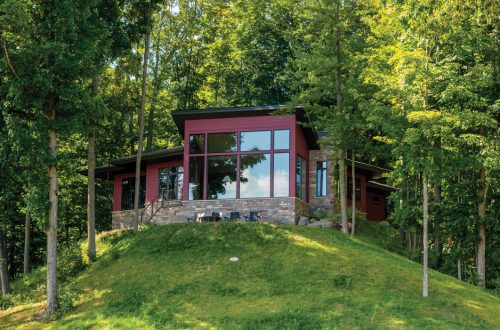

To realize the 192-by-46-foot-long, eight-unit project featuring 9,000 square-feet of sculptural space with six residential apartments and two live-work spaces surrounded by more than 160 trees in wooded serenity, Rafiuddin noted it boiled down to a finer appreciation for the landscape, the placement of the Quonset hut on the land, and an overall design that reflected a pastoral environment.

“At the same time, we wanted to use a structure—in this case a Quonset hut—that didn’t have symbolism behind it in terms of class,” Rafiuddin said. “It is something that is a little bit abstract, but also can be found in pastoral landscapes, can be found in agrarian places, and then the other thing with this, as far as lifestyle is concerned, we really wanted to promote this idea of what I call loft living, which is this idea that we create space for creatives and we let creatives determine how they want to live their life by giving them a blank slate.”

With 23-foot-tall ceilings and an intentionality in siting allowing for the radial journey of the sun to be experienced throughout the entirety of a given day, The Caterpillar focuses on volume and natural light to provide an almost gallery-like space for a broad range of users. Its interior is intuitive and simple in layout, where bedroom space and public, living space is organized around a central bathroom, kitchen, and closet island area that “internalizes uses that are short and ephemeral,” according to Rafiuddin. In reflection to the sun’s path, the bedroom space is located to the east and living space is situated to the west to take advantage of the daylight as it moves through the space.

“The Quonset hut allows me to more affordably create space. It allows me to offer to our residents very high-quality and generous space and the only cost is that I have this utilitarian-looking structure from the outside. It is the same way when you walk into a barn, oftentimes we are taken aback by how great the quality of space is in a barn and that is just space,” Kafka said.

“There is something spiritual about curves and with the Quonset hut, especially on The Caterpillar, we used a perfect half-circle. There really are no walls and there is no roof. The walls become the roof, which become the walls and go right into the ground. There is something extremely calming about being in a space like that and those are the two reasons I love the Quonset hut,” Kafka added.

Working with SteelMaster Buildings LLC of Virginia, The Caterpillar Quonset hut was engineered with custom fabricated windows and produced with 100 percent recycled steel. Considered disaster-resistant in design with an HVHZ approval for hurricane zones, the more utilitarian materiality of its exterior was tempered by a contextual wrap-around porch that takes cues from its surrounding community and a landscaped program that leverages trees and planting that not only regenerate soil, but also will mature in a tree canopy that can provide natural shade. Inspired by John Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” sheet music, Julie Bargmann of D.I.R.T Studio planted trees in a staggered pattern resulting in a thoughtful landscape where porches and pathways interact with its natural landscape. The landscaped program also integrated a clover bed rather than grass to reduce maintenance, while still offering a solution that behaves much like grass.

“She is exceptionally talented and has done many projects in industrial sites where the plantings she chooses are intentionally regenerating, like bringing nutrients back to the earth in conditions where they were lost, because of industrial usage,” Rafiuddin said. “In terms of that, we are essentially creating a habitat, but also bringing life back to the soil and the earth.”

For Rafiuddin, it is the space, light, and landscape that stand out as distinctive to him about the project, with an importance that extends beyond revisiting collaboration and what that looks like among industries. It is also about looking to unconventional building materials and methods—such as Ray and Charles Eames applying their bent wood technique from splints for wounded soldiers to furniture design—to the community itself and the people who will eventually call The Caterpillar home.

“We were trying to demonstrate these ideas and I hope this project illustrates that. In this case, we worked with SteelMaster and we wanted to innovate and I hope that it presents new opportunities for us to innovate, but also promotes to other architects and designers and developers that we can rethink and reinvent, but also work with industry. In this case it was a very small thing, it wasn’t as dramatic as what the Eames’ did, but in working with SteelMaster, we were able to truly come up with something innovative,” Rafiuddin said.

“And then as far as community, we designed this structure because there is this idea of community in mind. We know this is in a neighborhood in Detroit where community building is extremely relevant. We designed Caterpillar with this idea of community in the sense that with the landscape as well as a wrap-around deck on all four sides, as soon as you step outside of your unit, you are confronted as well as engaged with your neighbors if they are outside too. It presents an opportunity for interaction. It is an element of public space or social space. It is also very civic, because it starts to address the street and whoever is on the street. It is a reinterpretation of this porch culture or this community building through porch culture,” Rafiuddin added.

For Kafka, who noted the units were fully leased before its completion and has attracted a diverse group of professionals and creatives, The Caterpillar represents a more philosophical approach to urban development where space and light are central.

“I believe that we have already been given the most amazing design materials that we need. They exist already without us even touching anything: space and light. And architecture, to me, is how do we capture those two beautiful elements to give us life? We need space to grow and we need light to grow and we already have those two things out in the world, so my job as a developer is to create architecture that just so deftly, intelligently, and beautifully frames those elements, which we already have,” Kafka said.

“Light is a very important part of my projects and the quality of space is very important. I think about design in terms of how does our design, how do the materials that we choose interact with the space and the light that we are making. I don’t think about it in terms of luxuries and amenities,” Kafka added.

The Caterpillar was officially completed in March 2021 by the collaborative team of Prince Concepts, UNDECORATED, D.I.R.T Studio, Studio Detroit, and Jim Saad of Commercial Construction Management, or CCM, with photography work by Chris Miele and Jason Keen of Jason Keen Architectural Photography. Though the use of Quonset huts for residential and commercial use is not new, The Caterpillar posits an innovative solution for urbanism where horizontal density, contextual landscaping, and thoughtful interactions propel it into the future.

“I’m of the opinion that everything in the world is designed. Everything that exists should be design, so it should be a standard in my opinion,” Rafiuddin said. “To me, it’s universal. It’s a human right. It should be accessible to everybody and all designers have a responsibility to treat it as a human right. That is how I approach it, so in designing Caterpillar, it is not just about the residents, it is about the non-residents who are passing by. They should be confronted with something that is beautiful to look at, but also can appreciate it and there is humanity in it. It is also for them.”

First published in Great Lakes By Design: Ergonomics, 2022

Text: R.J. Weick

Photography: Courtesy Prince Concepts, Jason Keen